By Dr Mark Burgess

Australia has been a world leader in reducing tobacco use. Latest data from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) estimates that 11.6% of adults smoke tobacco daily. This has halved since 1991. Adolescents and young adults are more likely to have never smoked than any other age group (97% and 80%, respectively)(AIHW). What an amazing shift.

So, is it mission accomplished? Well not quite. Nicotine is addictive and rather than ‘changing its spots’ as some vested interests would have you believe it is rather more a ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’.

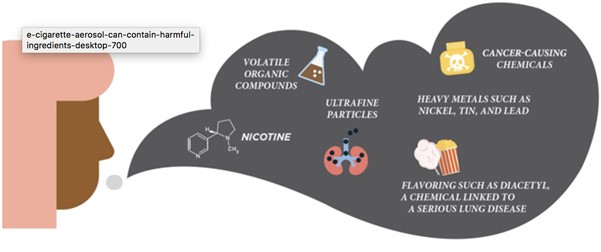

Younger people in particular are inhaling their nicotine differently – via e-cigarettes and vaping products. Also known by numerous terms including e-cigs, personal vaporisers, e-hookahs, vapes or juuls these devices are designed to deliver nicotine and/or other chemicals via an aerosol vapour that the user inhales. Most e-cigarettes contain a battery, a liquid cartridge and a vaporisation system and are used in a manner that simulates smoking. The liquid solution used in e-cigarettes can contain nicotine, but also flavourings and other chemicals including cannabis. Many e-liquids come in harmless sounding flavours that are attractive to young people such as lemonade, mango, lime and mint (RCH).

Increasing numbers of younger people are exploring these devices. Of those aged 18–24, nearly 64% of current smokers and 20% of non-smokers reported having tried vaping products, compared to 49% and 13.6% in 2016. Of all adolescent’s 14% have tried a vape with 32% of those having used in the past month. Most users initially vape out of curiosity not as a legitimate means of tobacco cessation (ADF).

Vaping manufacturers and some harm minimisation advocates argue that vaping products are safe and can help smokers shift away from tobacco. However, those using them are three times more likely to smoke tobacco than those who have not used them and former smokers who use them are more likely to relapse to current smokers (ADF).

Vaping products have not, unlike other nicotine replacement products (e.g. patches, gum, inhalers, lozenges), been assessed as safe and demonstrated as effective for tobacco cessation. Further, there is concern with their long term health risks. Despite this there is some very limited evidence that they provide a harm minimisation option for mostly older heavily addicted tobacco users and in people with mental illness who are more difficult to drag away from an ingrained nicotine habit (RACGP, TGA).

Nicotine exposure during the adolescence can harm brain development, which continues until about age 25. It can impact learning, memory and attention, and increase the risk for future addiction to other drugs (RCH).

Vaping products can poison children and adults through swallowing or skin contact. They can also be a danger to young children if inhaled, swallowed, or spilled on the skin. A young child can die from very small amounts of nicotine.

So, given the risk of vaping products how come they seem widespread?

It is currently illegal to purchase these products in Australia except with a prescription at a pharmacy. However, most products are currently purchased online and imported from overseas suppliers primarily in China. They are then distributed by numerous black market means and are proliferating in high school settings.

From 1 October 2021, however consumers will require a prescription from a doctor to obtain a vaping product from both an Australian pharmacy or from overseas. This is expected to place GPs in the difficult position of weighing up any harm minimisation benefit of these addictive products, that are not seen as first line for tobacco cessation, but are clearly being taken up at increasing rates by our youth and kids.

While this shift in nicotine delivery is unlikely to be as harmful as the tobacco eras, vaping products should not be considered safe. Like tobacco, it may be decades before we really understand their long term health consequences. In the meantime, nicotine in the guise of a harmless fruity vaping product, may have been introduced and seduced a whole new generation.

References:

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2021. Tobacco smoking. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/tobacco-smoking – Accessed 9/9/21

Alcohol and Drug Foundation. 2021. Vaping in Australia. https://adf.org.au/talking-about-drugs/parenting/vaping-youth/vaping-australia/ – Accessed 9/9/21

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Quick Facts on the Risks of E-cigarettes for Kids, Teens, and Young Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/Quick-Facts-on-the-Risks-of-E-cigarettes-for-Kids-Teens-and-Young-Adults.html -Accessed 9/9/21

Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Butler AR, Lindson N, Bullen C, Begh R, Theodoulou A, Notley C, Rigotti NA, Turner T, Fanshawe TR, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD010216. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub5.

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. 2021. Have GPs been supported for vaping to go prescription-only from October? https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/have-gps-been-supported-for-vaping-to-go-prescript – Accessed 9/9/21

Royal Children’s Hospital. 2021. E-cigarettes and teens. https://www.rch.org.au/kidsinfo/fact_sheets/E-cigarettes_and_teens/ – Accessed 9/9/21

Therapeutic Goods Administration. 2021. Nicotine vaping products and vaping devices. Guidance for the Therapeutic Goods (Standard for Nicotine Vaping Products) (TGO 110) Order 2021 and related matters https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/nicotine-vaping-products-and-vaping-devices_0.pdf – Accessed 9/9/21

Therapeutic Goods Administration. 2021. Nicotine vaping products and vaping devices: Frequently Asked Questions https://www.tga.gov.au/nicotine-vaping-products-and-vaping-devices-frequently-asked-questions – Accessed 9/9/21